This mostly talks about hole pattern in a fixturing surface. Philosophy of design approach.

For sure, there can be one variation of a tool that’s ‘best’ for scenario 1 and another for scenario 2. But i think the scheme i’ve come to is generalized enough to be useful discussion on a hole pattern to choose if you have ultimate freedom such as making a fixturing surface yourself.

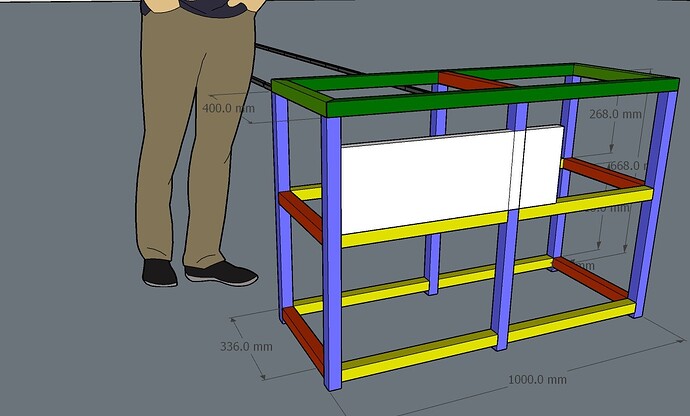

, , , This stems from my planning and playing with what i want to do with a 1" thick plate i bought. Surfaced; 686 mm X 408 mm (27 x 16 inches). Since i can’t have a table, this plate could be a half step. Part of me want to just cut it in half and have two (62 lb) strips, which might act as squares sometimes, and might join back together if needed to be the table approximation.

But i think i’m decided on keeping it one continuous piece (surface) since it’s machined flat and i don’t want to ‘break’ that.

, , , So, where do i drill the holes?

Looking to commercial examples, there seem to be two main versions of a cartesian (X-Y) grid. With either all rows and colums in line, or every second alternating by a half step.

A purely linear grid has some advantages. But i’m the kind of stubborn that i have to work through every choice myself. And when i set to exploring the characteristics (thus pros and cons) of the ‘offset-by-half’ alternating rows pattern, there’s the characteristic that not all holes are equally distant apart. As you can see above. Usable, but is there another way? I explored “what if all holes were equi-distant?”

, , , Hexagons are equidistant between all neighbouring holes.

And i got majorly side-tracked thinking that hexagonal hole pattern layout was the most advantageous.

See, a rectilinear grid is great … for rectilinear things. But if i’m allowed to say that “we often enough deal with other shapes” that maybe our hole pattern should deal with them easily too. A hexagon lets a round thing be located by three points that fall naturally the same distance from it’s perimeter. Etc. And an array of hexagons keeps sets of holes in linear alignment (there are still lines of holes at 90 degrees), though further apart than in a simple X-Y grid. So it actually includes both worlds (rectilinear, and beyond), so you could do things like locate a cylinder in reference to a length of square tube.

, , , However. Hexagons are just a special case of an array of triangles.

Which got me thinking whether including one more hole per hexagon, and making an array of triangles, was even better.

And what do you know, it is all of the same goodness, just better. But it’s not only a derivative of the hexagon pattern. Look again and it’s a version of the alternating-offset rectilinear pattern too. A version where all holes are equidistant. If you like, a version where the spacing of columns is determined by the hexagon, as opposed to determined by a square grid.

, , , This has additional outcomes such as being able to automatically reference 30 and 60 degrees (in addition to 90). Using the same tooling (eg stop blocks) at each of these angles. And being able to use triangle math in setting up fixturing (so, easily build triangles for one thing).

, , , There are two important characteristics of the equilateral triangle pattern. Which perhaps might be considered ‘lost’ from a pure square grid. Or perhaps ‘sacrificed for’, or in trade for, the other things like accommodating circles.

, , , One is that the distance between columns is not the same as the distance between rows. In one axis you’re dealing with increments of one size, and in the other axis another size. This could be accommodated for in the tooling used with such a pattern. (eg: pins with various size heads to take up the difference). But probably doesn’t need to be, and doesn’t have to be viewed negatively. To me it means i can work on a weldment that needs closer hole spacing by standing at one side of the fixturing plate, and work on a weldment needing greater hole spacing from the other side. More variation more better kind of thing.

, , , The other ‘consequence’ (of having lines of holes at 30 degrees, 60 degrees, and 90 degrees to each other) is that there aren’t any at 45 degees. This is a biggie. I haven’t sat down and explored whether tooling can re-incorporate this function. But perhaps there’s an aspect of ‘approach’ (fixturing method) that incorporates it anyway. If i’m going to be working with a 45 degree reference tool (a 45 degree ‘square’) in my arsenal anyway, then i do still have 45 degree capacity. I’m just not using the fixture plate itself for this in my fixturing approach.

, , , I then played with which orientation i would want the pattern on a rectangular fixturing surface.

In one ‘direction’ in the pattern, rows of holes are closer together than if the pattern (or the rectangular plate) is rotated 90 degrees. To me, one is superior. In one i can have the same number of rows and columns in my (4:6 ratio rectangle) fixturing plate. And have whatever loss of ridgidity happens due to holes be less pronounced in the longer axis of the plate (more space between holes in that direction), so that bending of my plate will be more even between length and breadth than otherwise.

, , , So my take-away from my re-designing the wheel (hole spacing pattern) here is that there’s a trade-off between a square offset hole pattern - with equal column and row distance and automatic 45 degree rows, and an equilateral triangle pattern - with 30, 60, 90 capacity; circle, hexagon, etc matching; and greater variability.

, , , But what am i missing? Is there some reason that straight up rectilinear pattern ( no offset) is better than the alternating offset pattern? And my triangulated version is moot? Is there another option still? Maybe golden ratio offsets? Did i miss some easy addition to the hexagons pattern that makes all dreams come true?

, , , I think i’m going to drill a grid pattern with equidistant holes. (On 100 mm centre to centre - to lessen the drilling) And force myself to develop tooling for this pattern, and learn how this tooling ACTUALLY has to be to deal with both circles and squares, etc.